Kajillionaire is the first feature film from writer-director Miranda July in which she isn’t also the star. It’s a different experience, stepping outside the frame and choosing instead to cast Evan Rachel Wood as her unconventional leading lady. But as the artistic polymath also tells us over a digital interview, she also “never [has] to stop looking at it from the outside.” The ‘it’ being an intimate portrait of a dysfunctional family of small-time scammers.

“I could go further,” July says during her conversation, “I could be more devoted to the actors… I wasn’t in there with them, in the fire.” This remove allowed her to be open to the final product, and letting it differ from her initial script. That and the confidence that comes from a long career of many hats.

“I’ve been now just making things in all mediums for a long time,” says July, a performance artist of all trades—from punk theater to sculpture installations, to a messaging app—who is used to wearing a dozen hats on a single project. “When you’re younger, you get really freaked out when things aren’t going according to plan; and by this point I think, ‘Well, there’s another way that’s gonna end up being the right way that’s different from what we planned.’”

That adaptability has served her especially well in the last six months of the COVID-19 pandemic, which delayed the release of Kajillionaire (among many other films) into theaters. Yet there’s a touch of self-fulfilling prophecy that July learned to embrace chaos in the current life-changing circumstances from her project about a brood of truly bad con artists whose attempts to score big earn them more problems than windfalls, with their half-baked schemes often spinning wildly out of control.

Though she wasn’t in front of the camera, July worked closely with Wood to develop the character of Old Dolio, the twentysomething daughter of a pair of lousy con artists (Richard Jenkins and Debra Winger), who nonetheless shares her parents’ fierce conviction in their scavenger lifestyle. Not only does Old Dolio not resemble July’s two avatars in her past films, Me and You and Everyone We Know and The Future, but her absence of femininity or softness distinguishes her from most twenty-something cinematic heroines.

“I’ve been wanting to work with [Miranda] for years and just jumped at the opportunity,” Wood says. “And then when I saw the kind of film she was creating, and the heroine that was Old Dolio, I was elated because you never get to see a leading lady look or act or sound like Old Dolio, and I had also never really read this script. And I’ve been doing this [for] over 25 years now, I’ve read a lot of scripts. So to actually be able to read a script that was so original I couldn’t compare it to anything else, that’s what excited me more than anything.”

With her lank hair, baggy tracksuit, and guttural voice, Old Dolio possesses the raised-by-wolves ferality of someone reared outside of mainstream society, especially with regard to hyper-feminized gender norms. Yet she’s clearly devoted herself to the Dynes’ scams, leaping, diving, and twisting herself into poses to evade security cameras—or just their long-suffering laundromat landlord.

“I’d never had a character who was gonna take some real work to get into,” July says. “I didn’t know if any of that was going to work, but I did think that rather than just arbitrarily come up with these physical restraints that it was important to sort of limit her intellectual state. I mean, she’s a full complete soul in there, but she’s not used to articulating, internally or externally, about her emotions.”

They workshopped the character together for about a week, with references and videos, so that they could build up what Wood describes as a “toolbox” once they got to set. “We had our own language that we had built for Old Dolio,” the star says. “Miranda could just call something out, and I would know what she was talking about. She would yell out, ‘Proud lion!’ ‘cause that’s one of the animals we had picked for Old Dolio, that she would emulate and have the same energy [as], and also when she needed to be slightly attractive for [Gina Rodriguez’s character] Melanie.”

That toolbox also gave them verbal shorthands for keeping Wood in-character; if it seemed like any feminine qualities (i.e., any of Wood’s own personality aspects) were coming through, July would yell out “hands” or “voice,” and her lead would remember to adjust her gestures or lower her voice.

In doing so, July says, they honed Old Dolio “until it was just physical. I was like, well, that sets her up inside her mind, her state, and from there she can probably do anything, was the hope. She could say these lines, she could do a tuck-and-roll.” While July had written in Old Dolio’s eccentric physicality before they began developing the character, she was gratified to see that Wood had no problem truly embodying the character.

“Evan actually could limbo, Evan could roll. You write all this stuff and then you’re braced to have to adjust to reality, but in Evan’s case, I never had to.”

Matching Old Dolio’s signature moves are the emotional and ethical gymnastics she must undertake as part of her family’s cons: whipping out the Catholic schoolgirl uniform when sweet-talking some rich marks; impersonating a stranger for a measly $20; forging signatures as easily as breathing.

“I related to Old Dolio in that way of a very unconventional upbringing and childhood,” says Wood, who has been acting for most of her life. “I was working since I was five, and sometimes seen more as a peer than as a child, and as a child star you can very easily confuse adoration and love, or performance and how it relates to love.”

Yet for all the necessary evils to which Old Dolio commits herself, she lacks the social intelligence to entirely pull them off; and her parents have no qualms about letting her know that they find her wanting.

“I think as Old Dolio understands it,” Wood continues, “love is a performance, in how well she does in these cons, and that [it’s] the only way to win her parents’ approval, and she convinces herself she doesn’t need anything else.”

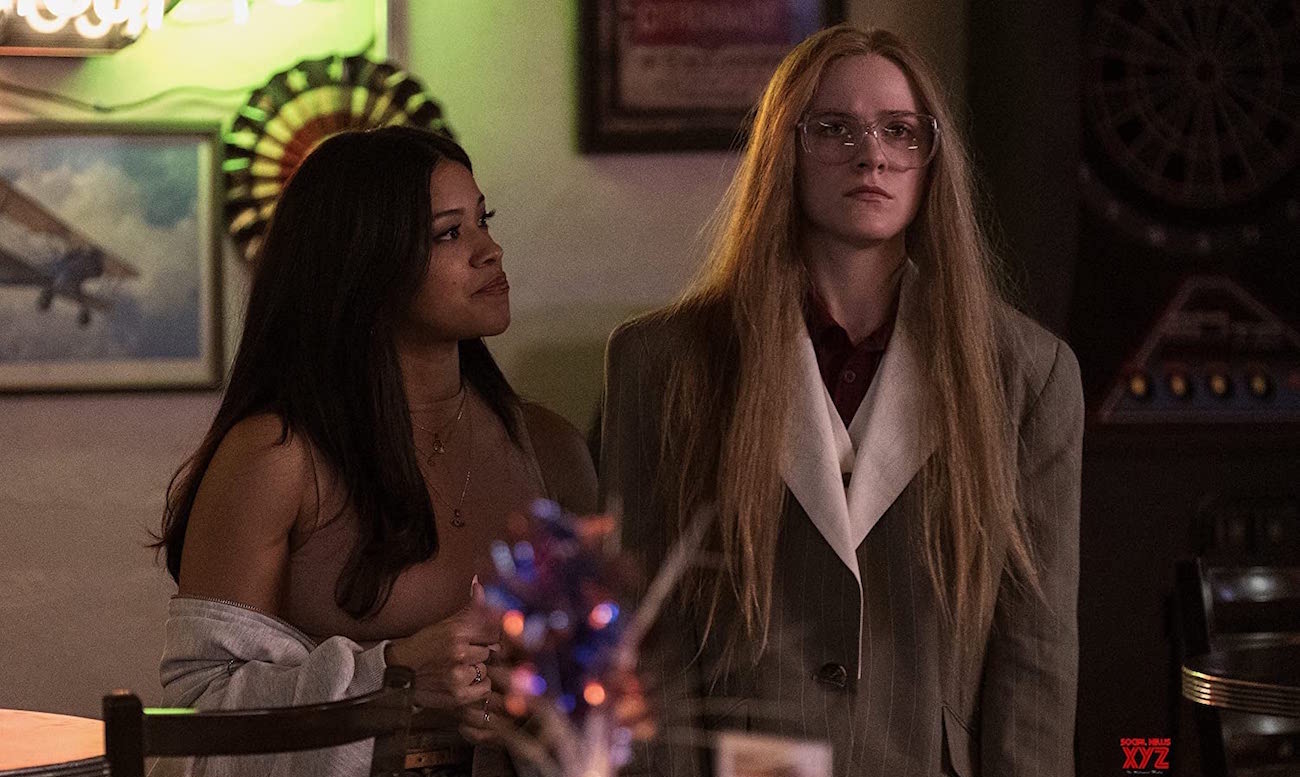

Like money, Old Dolio can get by on a dearth of love—until the Dynes meet Melanie (Rodriguez), a bubbly young thing who is all too eager to get in on their schemes. Flirty and feminine where Old Dolio is awkward and androgynous, quick-thinking in a way that reveals a whole host of life experience, Melanie allows the Dynes to expand the scope of their cons; but Robert (Jenkins) and Theresa (Winger) also begin to project on her all of the affection that they’ve always withheld from Old Dolio in the name of supposed authenticity. “You get the sense that she knows something is missing,” Wood says, “and she can’t quite put her finger on it until Melanie comes into the picture.”

The slow-burn queer romance between Old Dolio and Melanie helps the former begin to envision a life outside of the Dynes’ restrictive existence of diminishing returns, and to experience a love (or at least the sense of being wanted) that she has long been lacking. But not even July initially intended for first love to be part of Old Dolio’s journey of self-discovery.

“I actually had Melanie in there a little bit before understanding that there was a romance,” July says, “and so Old Dolio had this repulsion and this reaction against her, and the parents adored her. And then I was like, ‘Ah, wouldn’t it be [wonderful] to give this woman all the joy of being loved by her.’ I just wanted that for Old Dolio.”

“We agreed that it was so easy to fall in love with each other,” Wood says about developing the romance with Rodriguez. “We had that chemistry right away. And with a character like Old Dolio, you have to be incredibly forward, because she just doesn’t get it, or doesn’t want to. Again, she had no exposure to things. It’s all new to her. What I love is that gender is never spoken about, and sexuality is never spoken about, it just is. And it’s a part of the film, but it’s not what the film is about.”

The absence of gender that Wood found so freeing seems to have been by design, as July explains that she was aware of gendered tropes and expectations when crafting this romance.

“I always thought that if Evan’s character had been a guy, that the second Melanie entered the movie, you would know that there was gonna be a romance,” she says. “You could make that a real slow-burn, you could totally work against it and hide it, because you just know already, because of the formula, that they were gonna end up together. So I enjoyed treating it the same way, like not overly indicating, giving it the same artfulness—holding my cards like that, and trusting it, just trusting.”

Read more

One of the most artful moments in the film, which demonstrates not just the trust between July and her leads but also between Wood and Rodriguez, is Old Dolio’s dance. The scene is part of Melanie helping Old Dolio check off a list of formative life events she has been lacking up until now; the latter has never had the teenage experience of rocking out in one’s bedroom alone or with a friend. Yet the dance itself—set to the telephone hold music that is Old Dolio’s ersatz soundtrack for her own life—is entirely about Melanie being witness to Old Dolio’s pent-up anger and joy, poignantly inelegant yet hopeful.

Wood describes how she and Rodriguez each surprised one another: Rodriguez had not seen Wood rehearse the dance prior to shooting the scene; and when the cameras started rolling, the tears in Rodriguez’s eyes were completely authentic.

“She’s just that kind of actor,” Wood says. “She throws herself in, and she’s right there with you, just giving you everything.” Such moments also underscore why Wood feels like Kajillionaire was at times like shooting two different movies.

“There was the one with the Dynes, and there was the one that Gina and I were doing. And that was always so beautiful and tender and sexy and heartbreaking. That’s when we really got to lean into the heart and soul of the film.”

Arguably, what most identifies Kajillionaire as a Miranda July film is the surreal imagery of pink soap bubbles cascading over the wall of the Dynes’ shabby rented residence: an instantly familiar sitcom shorthand for a situation about to get out of hand, but that in July’s framing becomes strangely soothing. What began as the explanation for why they were able to live somewhere with such cheap rent—every day they must clean up the bubbles, only for the laundromat to inevitably produce more—took on a dreamlike beauty as July decided to link the bubbles to a recurring visual device in her films. In the case of Kajillionaire, the director says the bubbles “tap into that primal anxiety… they have to dispose of it in this Sisyphean way, but it keeps coming.”

Sisyphean could perhaps also apply to the staggered timing for Kajillionaire’s release. Following the film’s production, Annapurna Pictures declared bankruptcy, and July was forced to find a new distributor at Sundance; they did in Focus Features. The movie premiered at the festival in January 2020, weeks before whispers of COVID-19 began permeating America, and once the nationwide lockdown and quarantine began, its June release was pushed to September. While July acknowledges that she was of course disappointed “not to get to do my well-laid plans for this movie,” watching the film finally get released six months into COVID has given her a change in perspective.

That was due in large part to hearing from people within the last several weeks who were watching Kajillionaire for the first time during quarantine. “There was no other version of the movie to them but the one that they saw now,” she says. “It’s not that it’s a different movie, but there’s so many things in it that they spoke so intensely to me about—just a lot of little resonances with this time, and I think that made me feel like, ‘Well, maybe I was making it for us now.’”

July has found the silver lining on the metaphorical soap bubbles, in that Kajillionaire might be coming out exactly when it is supposed to. “That is the reality of what has happened,” she says, “so there’s no point in thinking that six months ago was my true time—like, no, I have to own it, this movie is for now.”

While filming Kajillionaire, Wood was also wrapping up three seasons’ worth of character arc for android Dolores on HBO’s Westworld. “There’s certainly parallels there,” Wood says of Dolores’ becoming self-aware and breaking out of her own loop compared to Old Dolio’s story. “I think that journey inward and that journey to consciousness is part of all of our journeys.” But her real takeaway is about breaking out of toxic loops, plus concerns of family as a whole.

“I’ve heard Miranda speak about families and how each one of them is its own mini-cult, in that they all have their own set of rules and morals and standards,” she says. “Each one is a little different, and we all go through a moment where we have to start defining ourselves separate from our family: what that looks like and who we really are, and what we really want. And sometimes that does not match up with the family that we have been raised in, and it can be quite jarring and traumatizing. Especially when you make the decision to share your true self with your family. I know queer people can certainly relate to some of this, and that idea of discovering who you are and sometimes having to leave the only thing that you’ve ever known.”

Wood hopes that Kajillionaire moves audiences to reconsider their childhoods and their own parenting styles, but her greatest wish is that it reaches the people who may never have seen themselves reflected back in film before: “I hope if there’s any Old Dolios watching, that they feel seen, and like they got to be the leading lady.”

Kajillionaire will be released in theaters on Sept. 25.