This article contains minor spoilers for The Protégé and Nikita.

The TV landscape has always been ahead of movies when it comes to giving women—and other underrepresented identities—a shot. This is probably because there has traditionally been less money to be made on TV, so the rich, mostly white men who rule Hollywood have left TV to a slightly more diverse crowd of behind-the-scenes talent to tell slightly more diverse—especially on less “important” platforms like The CW.

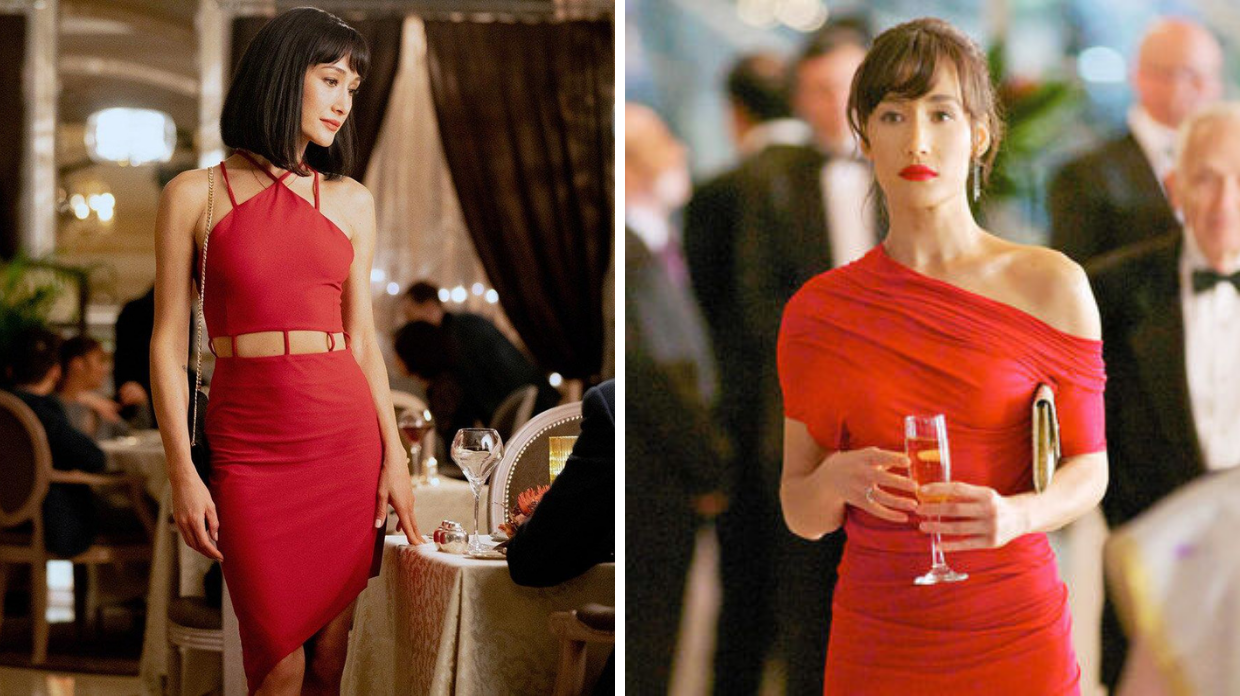

Action flick The Protégé, released in theaters last weekend, tells this story too well. The film pairs Casino Royale director Martin Campbell with proven action hero Maggie Q, and it should be a shoe-in for a good time. Unfortunately, a terrible script results in a 109-minute reminder of just how good Q’s underrated action TV series Nikita truly was, and just how much kinder action TV has been to women than the world of action movies in the last decade.

The Protégé is Infuriatingly Bad

The Protégé is an exercise in casting several charismatic actors and seeing how many terrible tropes can be piled on top of them before the performers break under the clichés’ weight. The answer is a lot, because Maggie Q, Samuel L. Jackson, and Michael Keaton are goddamn professionals.

In The Protégé, Q stars as Anna, a Vietnamese assassin found by hitman Moody (Jackson) as a child and trained to join the found family business. Thirty years later, when Moody is killed by a mysterious Big Bad, Anna goes back to Vietnam to find his killer and becomes tied up in a convoluted conspiracy.

Yet despite a large chunk of this movie is both set and filmed in Vietnam, the film’s world is populated almost entirely by American characters, including a Da Nang-based biker gang headed by Robert Patrick and composed of other white men. Rather than delve into the rich texture of Da Nang, one of the Vietnam’s biggest cities, The Protégé uses the city as a backdrop to be coded with colonialist assumptions of danger and lawlessness. One need look no further for how the film feels about its setting than the following line delivered by Patrick’s Billy Boy: “Vietnam has always been a place of death. Only the lucky ones make it out alive.” It’s particularly disappointing for a film led by a Vietnamese American actor to fall down so hard in its Vietnamese representation.

Read more

While some viewers may celebrate the arrival of Keaton’s Rembrandt, a fixer for criminals situated as Anna’s equal on the bad guy’s team, that celebration would be premature. The film forces a Mr. and Mrs. Smith dynamic on the two that not only severely undercuts their believability as professional killers but also leads to the truly horrific line: “You point a gun at my pussy, and then you ask me to bed. I like your style.” (Q didn’t have to put up with this kind of shit in Nikita.)

The film doesn’t bother giving the characters a believable motivation for their dull flirtation, which traverses a 27-year age difference. Instead the movie seems confident in the infallibility of the all-too-common movie rule that posits a hot woman must be attracted to the movie’s white male lead and presumed audience surrogate. That this responsibility is forced on Q in what should be her film speaks to just how firmly these sexist tropes are entrenched in our film language. For those who need a point of comparison, look no further than the other (better) screen story that sees Q playing a badass assassin, out for revenge…

Nikita: One of TV’s Best Action Dramas

While The Protégé is a movie that is far worse than it should be, Nikita was a TV show that was always far better than it was given credit for. Based on the ’90s TV series La Femme Nikita (which was, in turn, based on the French film Nikita), the CW action drama ran from 2010 to 2013 and starred Q as an assassin gone rogue and looking to take down the shady government agency, known as Division, that trained her. With Jackie Chan-trained Q as its star, and in a pre-Arrow TV landscape, Nikita easily had some of the best fight scenes on TV. It also casually centered an Asian American star in a time when that was even less common than it is now.

While Nikita‘s action was fun and impressive to watch in its own right, that only gets you so far in action-driven storytelling. Any action series hoping to sustain itself must ground that action in character. Nikita did this in part by centering a relationship rather than a lone hero. Nikita shares protagonist duty with Alex (played by Agent Carter‘s Lyndsy Fonseca), a young woman recruited by Nikita to become a double agent within Division. While The Protégé ostensibly sets itself up around a core relationship—the one between Anna and mentor Moody—it rarely bothers to show us what the connection between these two actually looks like, or even how Moody’s death impacts Anna past her desire to kill whoever is responsible. This is especially a shame as, in the few scenes that let Q and Jackson breathe, there’s some great chemistry between the two actors.

While The Protégé barely bothers with its most important relationships, Nikita directly explored just how messy spycraft can get when personal relationships and past trauma is involved. There’s a tendency in female-fronted action stories to give the Smurfette woman assassin the same stoic, invincible demeanor as the stereotypical Male Action Hero, seemingly along the principle: anything you can do, I can do better. And I get it, I do. But, for my money, the best female-fronted action flicks (and male-fronted action flicks, for that matter) are the ones that allow their protagonists to be affected by the violence they are enacting and that is being enacted upon them.

For a cinematic equivalent, one need look no further than Campbell’s own masterful Casino Royale, which effectively contextualizes James Bond’s action with the character’s obvious trauma without losing the fun of the franchise. As Nikita progresses, especially in its first season, we see Nikita torn between her goal to take down Division and her responsibility to Alex. It makes for riveting stuff, and that’s without taking into account the rest of the tangled interpersonal web that makes up Division.

Action only matters if it has stakes, and those stakes must be grounded in character at some level. If a protagonist is largely unaffected by the action they are a part of, then so are we as viewers. If a story doesn’t do the work to demonstrate what an action hero cares about then there are no stakes to them achieving it or not. In Nikita, we care about the outcome of the fight scenes because we care about the characters—often, on both sides of the fight. We care about Nikita and Alex’s goal to take down Division because we see how much harm it is has done to both of their characters, and to the world at large. But we also care about their wellbeing, and the wellbeing of their relationship, which complicates how every single fight scene plays out. The same cannot be said for The Protégé, which never sells us on any of its characters, let alone their relationships to one another.

Read more

It makes sense that Nikita would be better at telling a new, interested action-driven spy story than The Protégé. The CW series may have had far fewer resources than a Hollywood movie, but it also had something The Protégé never bothered to invest in: diverse behind-the-scenes creative talent. While Nikita was showrun by Craig Silverstein (who would go on to create another underrated TV show in Turn: Washington’s Spies), its writing team also included women and/or people of color like Amanda Segal, Kalinda Vazquez, Kristen Reidel, and Albert Kim, who will be showrunning Netflix’s live-action Avatar: The Last Airbender series.

While it’s of course possible for writers to imagine complex interiority for characters whose identities are different from their own experiences, that’s not often how it shakes out in Hollywood, which is still largely run by white men from financially privileged backgrounds. When TV shows and movies hire people who fall outside that very narrow demographic (and those people are supported in their storytelling), fresh stories tend to happen organically by virtue of the greater diversity in perspective and lived experience at the storytelling team’s disposal.

Filmmakers have built a genre on action movies featuring male leads who punch their way out of problems, but the best action movies have always been the ones that give those problems emotional stakes. While trope-y action films centering unaffected white man are a story failure, trope-y action films centering unaffected woman of color can be an even greater missed opportunity.

It’s past time to start reimagining feminist storytelling as something other than slotting women of color into tired tropes built by and for white male protagonists. Maggie Q is one of the best action heroes of her generation and, especially post-Nikita, it’s a shame that she hasn’t had more opportunities to demonstrate that.