When all is said and done, the Harry Potter book series is 1,084,170 words long. So it’s only natural that, in fitting each novel into a roughly two-hour film, some story elements would need to fall by the wayside. Characters and entire subplots are chopped into bits and pieces to fit the new, abridged narrative structure. Peeves disappears entirely. This is why so many fans of literature always seem to prefer the book to the movie—how could they not, with all the sumptuous little details that text invariably seems to add to the experience?

But while you may be able to come to terms with the fact that the plot needs to be truncated to meet the needs of cinema, it’s incredibly frustrating when characters are changed, often for the worse, when they’re still given a significant amount of screen time that could be utilized in a more faithful adaptation. There are plenty of Harry Potter characters who, in their translation to the screen, die by a thousand cuts, and whose effectiveness within the story is blunted by inexplicable changes that completely redefine who they are, especially in relation to other characters. Here are the movie characters who deviate in the most frustrating ways from their book counterparts…

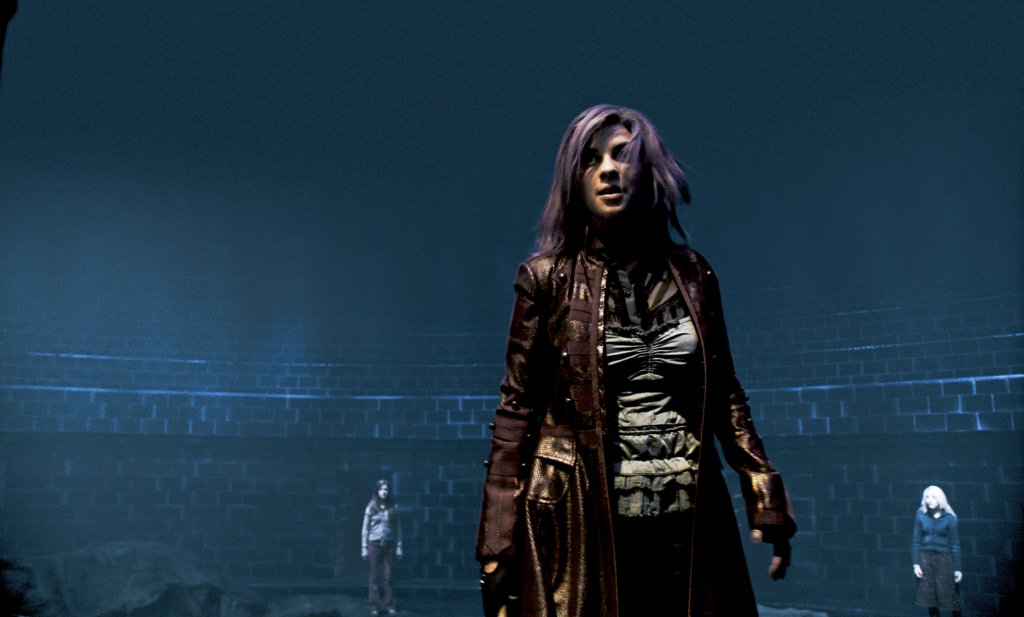

Nymphadora Tonks

That Tonks first shows up in the movies looking like a 14-year-old who tried to dye her hair purple using grape Kool-Aid and it has already half faded out (instead of a bright, vivid lilac like it is in the books) may be a small thing, but it’s a harbinger of how her character will be presented in the films. As written, Tonks is a bold, irreverent wise guy whose comic antics would give Fred and George a run for their money. But, in each of her appearances in the later Harry Potter films, it’s as though the joy and energy has been sucked out of her.

Read more

She’s supposed to be the new addition to the Auror crew, a rookie who is eager to finally be out in the field, but from the very beginning, she already comes across as serious and battle-worn. We get one scene with her using her power to change her face at the dinner table for a laugh— which is presumably more to introduce the concept of a Metamorphmagus than to really establish her sense of humor—and maybe a single quip with Mad-Eye Moody, and that’s it.

In the books, Tonks is a bright, energetic twenty-something, but you wouldn’t know it from the way she’s immediately lumped in with the older group of witches and wizards. And because she’s so serious right from the jump, it changes the dynamic of her romance with Lupin: now, they’re just two warriors who fall in love, whereas before there was a touching element of her bringing light and youthful energy to his life.

Barty Crouch, Jr.

Well, what to say about good old Barty Crouch? In Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, he is introduced as the son of a high-ranking Ministry wizard who throws his lot in with Voldemort in a stupid, pointless show of loyalty and cruelty by torturing Frank and Alice Longbottom even after Voldemort had already disappeared. That he is still a teenager at this point, pale and terrified-looking, has an impact on how we view the court proceedings: no matter how terrible a person is, it’s emotionally effective to show him crying for his parents, driving home how young and easily manipulated he is. It’s a reminder that Voldemort tore apart families in many different ways, not just by murder and torture, but by corrupting his young followers to the point where they are completely indoctrinated and lost to their parents.

David Tennant’s performance, however, has none of this subtlety. From the moment he turns up on camera, gnashing his teeth and incorporating a strange, snakelike tic with his tongue, he essentially puts up a giant neon sign saying, “VILLAIN.” His Barty Crouch is almost cartoonishly evil, and much older, so all the nuance and any sense of vulnerability in his character is lost.

Sirius Black

There’s a lot to love about Gary Oldman’s portrayal of Sirius Black: he gets a lot of the fatherly bond with Harry right, and the idea that Sirius sometimes forgets that Harry isn’t James is well-executed. But the book version of Sirius had a roguish, devil-may-care quality, even after years in Azkaban, that Oldman is somehow lacking. As we see him in the film Prisoner of Azkaban, he leans into mania during the Shrieking Shack scene when he confronts the trio, whereas in the book, he’s almost chillingly calm and composed, full of steely determination and a heart set on revenge.

Read more

The later films fail to capture either his sardonic wit or his mercurial nature, as he is trapped in the house that made him so miserable as a teenager. All of the sequences that feature the Order of the Phoenix are hurt by a need to be incredibly serious to show that the threat of Voldemort is real, failing to grasp the nuance that, just because you’re involved in important and dangerous work doesn’t mean that you’re somber and humorless all the time. This tendency hurts a lot of the adult characters, but especially Sirius, who has few opportunities to showcase the extroverted qualities that best define him.

Ron Weasley

Let’s talk about how the films siphon away all of Ron’s good character traits and give them to Hermione, leaving him a gibbering mess useful only for comic relief. In the books, the trio is well-balanced: they all bring different kinds of intelligence to the table. Hermione is book smart but can sometimes struggle to put her knowledge to practical use, as we see in Sorcerer’s Stone where Ron tells her to start a fire to escape the Devil’s Snare and she panics, saying that she doesn’t have any wood. Ron, by comparison, is a strategist. He’s notably the best out of the three at chess, and can think on his feet in terms of tactics in a way that neither Harry nor Hermione are capable of.

That’s book Ron, though. Movie Ron never stood a chance as soon as the filmmakers realized that Rupert Grint was funny, and screenwriter Steve Kloves admitted a marked preference for Hermione as a character. He’s not only stripped of his intelligence, but he’s not even given the dignity of maintaining the practical knowledge he would have amassed having grown up in the magical world. When Draco Malfoy calls Hermione a Mudblood in the book version of Chamber of Secrets, Ron is the only one of the three who fully grasps what an offensive slur this is (and, to his credit, immediately reacts in her defense). In the film, inexplicably, Hermione is already fully aware of the cultural weight of the term. If the movie versions of Harry and Hermione don’t need Ron to explain wizarding things to them, and he lacks his uniquely strategic mind, what purpose does he even serve?

Ginny Weasley

Look how they massacred our girl! In terms of disappointing book-to-film character adaptations, Ginny is perhaps the most egregious. In the book, she is a pure force of nature. She moves on from her puppy dog crush on Harry and becomes her own person, realizing that there’s no point sitting around waiting for someone who may or may not ever like you back. Ginny is confident, powerful, and sex-positive in a way that few of J.K. Rowling’s prim characters manage to be. She dates around and gives Ron an earful when he starts to judge her. Ginny is genuinely funny, and you can see the similarities between her and older brothers Fred and George.

But none of that is in the movie: Ginny is depicted as Harry’s awkward love interest and nothing more. She gets one or two moments that showcase that she’s a powerful witch, and we see her dating other characters (mostly so the film can show that Harry is jealous), but that’s kind of it. Bonnie Wright is sweet and she does everything that’s asked of her, but her performance as Ginny doesn’t have any of the vivaciousness that people loved the book character for.

It certainly doesn’t help that they utterly mangle the romance between Harry and Ginny. Case in point: their first kiss. In the book, Harry kisses Ginny in a moment of instinct while celebrating her achievements on the Quidditch field. In the movie, they share a tentative, barely there kiss in the Room of Requirement that Ginny initiates and then says, “That can stay hidden up here too, if you like.” Somehow, disappointing doesn’t quite cover it.