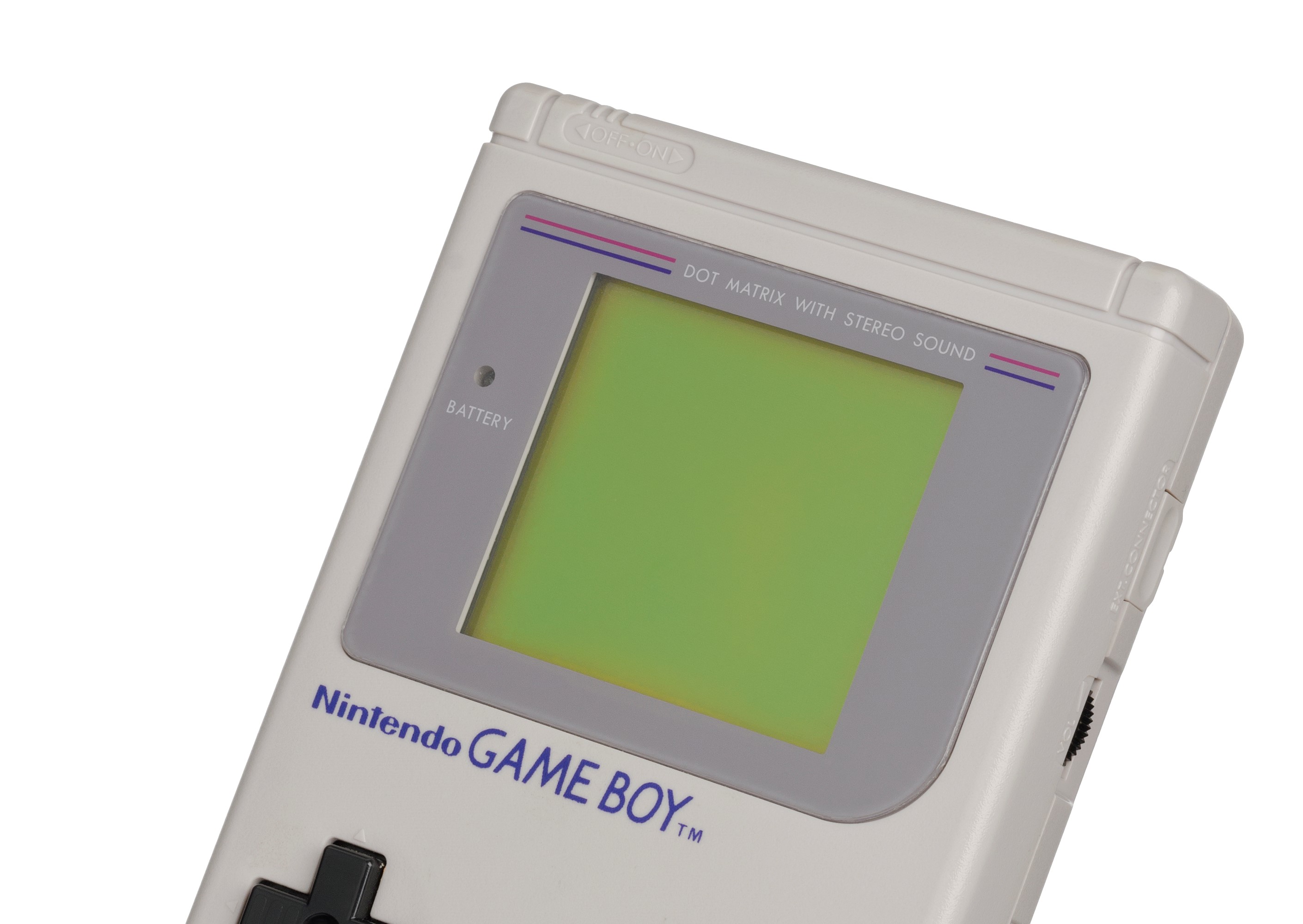

While the Nintendo Game Boy is one of the most influential and successful pieces of video game hardware ever, it’s hard to look at the device these days and not wonder why its graphics were so green.

It’s funny, but I’ve found that even some of those who grew up with the Game Boy can still be thrown off by the impact of its display. You probably remember that the original Game Boy’s screen was green, but you may have forgotten just how overwhelmingly green the handheld’s screen truly was. It’s just such an off-putting and unappealing (at least by modern standards) color choice that Nintendo obviously never really tried to repeat.

So why did they decide to make the Game Boy’s screen green in the first place?

You’re probably tempted to assume that the Game Boy’s screen and design can simply be attributed to technological limitations. A quick look at pretty much every handheld gaming device that preceded the Game Boy seemingly confirms that assumption. Actually, compared to devices like the Game and Watch and early Tiger Electronics handheld games, the Game Boy’s screen looks positively advanced.

However, it’s not entirely accurate to blame the Game Boy’s green screen on the idea that there were simply no better alternatives available at the time. After all, the Atari Lynx handheld gaming device was released the same year, and its screen supported full-color graphics. You also can’t say that Nintendo wasn’t aware of the existence of that technology. The creators of the Handy Game device (which eventually became the Atari Lynx) tried shopping their technology to Nintendo (as well as other major game companies), so Nintendo obviously knew there were more advanced alternatives out there that offered far more power and more advanced visuals.

There’s a big difference between “power” and “practicality,” though, and understanding the difference between those concepts is the key to understanding the philosophy behind the Game Boy’s green screen.

See, Game Boy designer Gunpei Yokoi and other key members of the Game Boy design team were all about keeping things cheap and practical. I know that sounds like something corporations say whenever they want to justify maximizing their profits and screwing over consumers in the process, but that wasn’t the case here.

In fact, the Game Boy team rightfully recognized that handheld gaming devices of that era needed to be simple in order to be consumer-friendly. After all, the Game Gear and Atari Lynx may have been more technologically advanced, but their base costs were notably more expensive. More importantly, those handheld devices required more batteries and “boasted” battery lives that were atrocious even by the standards of that era. It’s also hard to call the Game Boy a cheap console with a straight face. Many original Game Boys still function today, and there’s always that famous story of the Game Boy that reportedly survived a bombing during the Gulf War. Those things were built to last.

More importantly, Yokoi was a big believer in a design philosophy commonly known as “Lateral Thinking of Withered Technology.” Basically, he believed that Nintendo was often better off finding new ways to use older, cheaper, and more proven technology than they were trying to deal with the expensive growing pains of figuring out new technology. His beliefs on that matter weren’t always popular (the Game Boy was even mocked internally at Nintendo for its weak power and simple design concepts), but they obviously worked out in the Game Boy’s favor. For that matter, Nintendo still utilizes elements of that design philosophy to this day.

All of that helps explain why the Game Boy’s designers didn’t even try to offer full-color graphics, but why did they settle on that weird green screen? Well, there are really two good answers to that question.

The first has to do with the popularity and availability of dot matrix display technology. If Nintendo was looking for withered technology that they could apply lateral thinking to, they could hardly choose a better piece of withered technology in 1989 than a dot matrix screen. While alternatives to dot matrix technology were becoming much more popular at the time, that strange green glow those screens produced had become an accepted part of ‘80s technology culture. Furthermore, dot matrix screens may have been limited, but many developers knew exactly how to work with them. That really allowed them to ignore the temptation of trying to make a console-worthy experience work on a handheld device and instead focus on what kind of games made sense for the portable Game Boy and its older technology.

However, the relative brightness of the Game Boy’s screen may have been one of the biggest contributing factors to the final decision to “go green.” After all, properly backlighting handheld game consoles has historically been quite difficult (even the Game Boy Advance suffered from backlighting issues), and trying to backlight a handheld game console in 1989 would have torpedoed Nintendo’s plans to keep the Game Boy cheap and accessible. Again, just look at what happened to the Atari Lynx and Sega Game Gear.

So, while that weird green glow may have not been the perfect solution to that particular problem, it did offer a way for Nintendo to provide a somewhat unusual second source of light. The basic idea was that black pixels on a green background are slightly easier to see compared to black pixels on a white or grey background whenever you’re playing in an environment that doesn’t offer ideal lighting. The slight advantages the green screen offered in that area must have made it easier to justify the dot matrix decision the Game Boy design team had seemingly already committed to.

Indeed, while many were happy to see that the Game Boy Pocket eventually replaced the Game Boy’s “pea soup screen” with a black and white alternative, you could make the argument that the Game Boy Pocket really shows you why the Game Boy’s designers opted for that green background in the first place. The Game Boy Pocket’s screen is certainly better than its predecessor’s, but it doesn’t represent the kind of obvious and drastic improvement that would have easily justified Nintendo ruining the Game Boy’s battery life or raising its cost just to avoid going green.

In short, you can attribute the Game Boy’s green graphics to a strange combination of innovation and practicality. While it’s more than a little jarring to try to play a game on an original Game Boy screen today, it’s also hard to deny that the green screen made a lot of sense at the time, helped the Game Boy become as successful as it was, and, to be perfectly honest, gave the device an identity that is easy to be nostalgic for despite how “ugly” some claim that screen was.