When you hear the name “Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty,” there’s a good chance that you simply think of the game itself and your memories of playing it. However, there’s an equally good chance that the mere mention of that name instead gets you thinking of its controversial debut and the ways it ushered in a new era of fan backlash.

Granted, that’s a bold statement. After all, it’s not like fan backlash was a new concept at the time that Metal Gear Solid 2 was released to a…divided reception in 2001. Just look at what happened to The Phantom Menace just two years before. The idea of fans of a franchise (or a creator, or a concept, or what have you) rising up against a certain piece of work in intense ways is about as old as entertainment itself. Metal Gear Solid 2 certainly wasn’t the first instance of that concept.

Yet, there are specific ways that the backlash against Metal Gear Solid 2 would offer a grim preview of the pop culture climate we currently live in.

The easiest way to understand why Metal Gear Solid 2 was so controversial is to break the game down into three smaller sub-controversies:

- The game’s story/storytelling and ending.

- The reception to MGS 2‘s demo v.s. the game itself.

- The decision to “swap” MGS 2’s protagonist early on in the game.

Let’s start with Metal Gear Solid 2’s story since that particular controversy kind of feeds into the other debates.

We’ll dive a little deeper into Metal Gear Solid 2’s plot as we go along, but for now, it’s enough to know that the bulk of the game tells the story of a FOXHOUND agent who must infiltrate a secure facility in order to rescue hostages from terrorists with unique (and bizarre) powers/personalities.

If that sounds like an almost exact copy of Metal Gear Solid‘s plot…well, that’s because it kind of is. MGS 2 intentionally copies and pastes much of the previous game’s plot in order to tell a fourth-wall-breaking “meta” story. Specifically, it deals with how little control we actually have in video games and how powerful the illusion of control can be in many aspects of life. For much of the game, though, players have no idea that’s what’s happening. Much of the experience just feels like an odd retread of the previous game with a few new characters, a different setting, and a couple of gameplay twists.

Ideally, Metal Gear Solid’s ending would have clarified the game’s true intentions and given players an “aha” moment that made it easy for them to reexamine and appreciate everything that happened before (kind of like what we saw with BioShock’s big twist ending). The problem is that there’s nothing “easy” about MGS 2’s ending. The game tries to explain its true intentions via a lengthy conclusion that arguably tries to cram too many ideas into incredibly long cutscenes and other non-interactive (or barely interactive) storytelling segments. Said segments are also filled with vague philosophical ramblings that can often sound like gibberish to anyone just looking for some kind of major plot point to latch onto. Even if players were interested in (or sympathetic to) the game’s ideas, they didn’t buy a video game to attend a lecture.

Generally speaking, that’s the biggest point of contention when it comes to Metal Gear Solid 2’s storytelling style. While Metal Gear Solid certainly featured its share of cutscenes, strange plot points, and non-interactive sections, MGS 2 took things to a whole new level. There are almost six hours of cutscenes in MGS 2, and many of them feature philosophical musings, misdirections, and other storytelling devices that do everything but advance the story in a traditional way. There are many times when it feels like the game is talking at you rather than really telling a story. It’s easy to get lost if you’re not really tuned into everything that’s happening.

Mind you, expectations for Metal Gear Solid 2’s storytelling (and every other aspect of the game) were seriously warped by the popularity of MGS 2’s playable and non-playable demos.

Hideo Kojima stole the show at E3 2000 by revealing an extensive demo of Metal Gear Solid 2 that got everyone buzzing. Those who said the demo looked too good to be real had to eat their words when Konami made the surprising decision to include a playable demo of MGS 2 with every copy of the 2001 game, Zone of the Enders. Against all odds, that playable demo looked and played better than the already impressive non-playable demo that was released a year before.

Metal Gear Solid 2’s hype was already at a fever pitch at the time of Zone of the Ender‘s release, but that demo sent things into overdrive. It was a stunning (and surprisingly long) playable demonstration of a major upcoming game that somehow exceeded all expectations. The game looked great, it played much better than its predecessor, and it told a tight (though still strange) narrative that was clearly setting up a bigger adventure. In the minds of many, that demo confirmed that MGS 2 was going to live up to all expectations. Fans couldn’t wait to see what was next for the beloved series protagonist, Solid Snake.

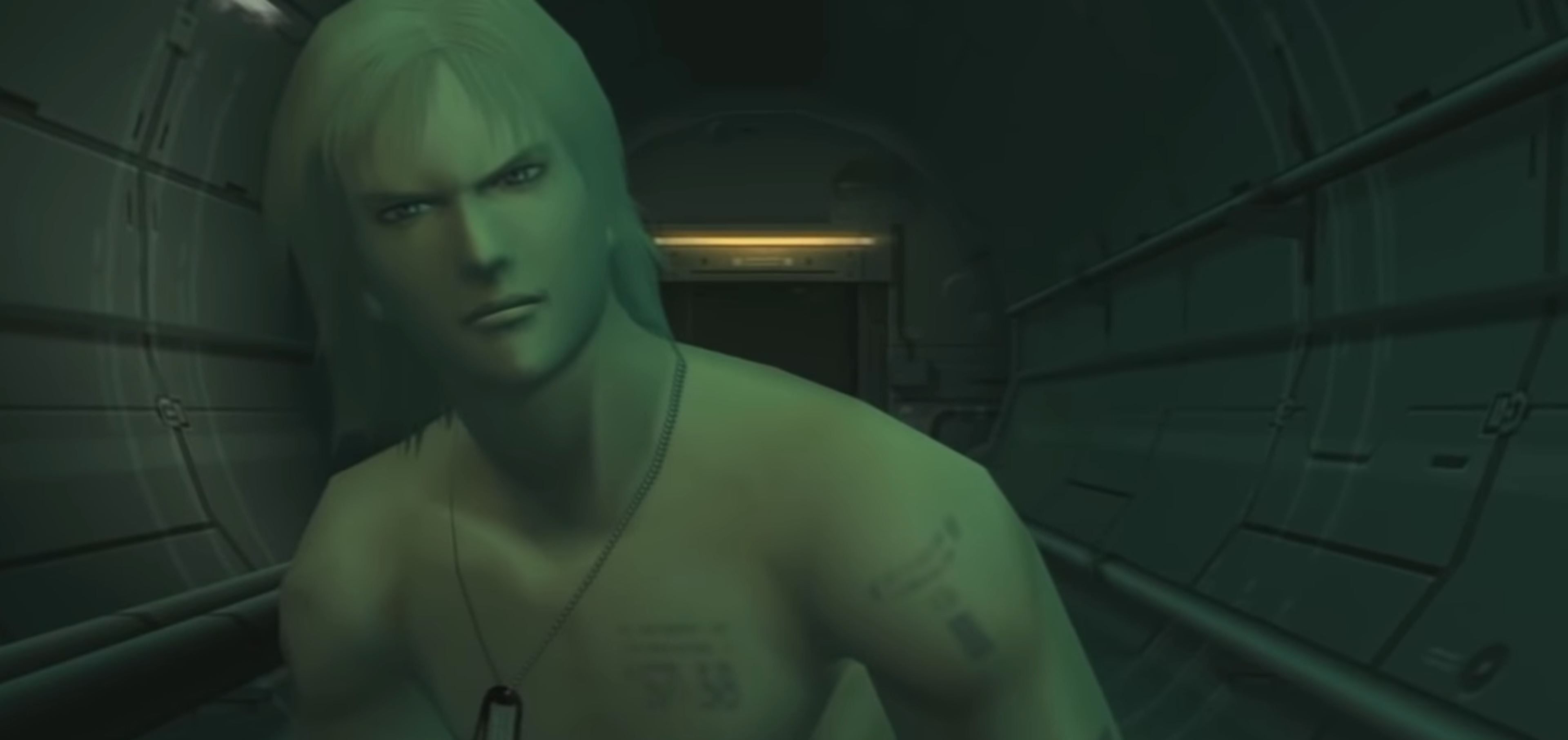

Of course, that brings us to the big Metal Gear Solid 2 controversy: the fact that the majority of the game doesn’t actually star Solid Snake but rather a new protagonist named Raiden.

The first time you actually control Raiden in Metal Gear Solid 2 is certainly odd, but it wasn’t necessarily a dealbreaker. I’m willing to bet many gamers at the time simply thought it was some kind of detour that would eventually allow them to play as Solid Snake once more. The fact that Solid Snake actually shows up later in the game (as a character named Plisken) only seems to confirm that theory.

That swap never happens, though. You spend well over 75% of Metal Gear Solid 2 playing as Raiden. While the decision to replace Solid Snake was always going to be jarring and divisive, it should be noted that a lot of players also simply hated Raiden as a character. They found the rookie operative to be whiny, weak, and step down from Snake in just about every way. To make matters worse, MGS 2 still prominently features Snake (as well as some other major characters from Metal Gear Solid). Because of that decision, it sometimes felt like you were just a side character in the real adventure.

There are counterpoints to all of those arguments, and we will get to them. For now, though, it’s more important to realize that Metal Gear Solid 2 was a strange kind of sequel that seemingly did everything it could to go against what people expected from it despite the fact that everything fans had seen, heard, and played of the game so far was going to match (or surpass) those same expectations.

At the time, there was nothing else on the market (especially in gaming) quite like that. Now, though, the story of Metal Gear Solid 2‘s controversial debut probably feels all-too-familiar even if you know next to nothing about the game itself.

Metal Gear Solid 2 Ignited the “Give Fans What They Want” vs. “Subvert Expectations” Debate

Metal Gear Solid 2 obviously wasn’t the first sequel to disappoint fans. There had been countless bad sequels to great movies and games released before then. It also wasn’t the first sequel to be wildly different from the original. Everything from movies like Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 to Gremlins 2 and games like Super Mario Bros. 2 and The Legend of Zelda 2 offered wildly different experiences from what came before. Those sequels weren’t exactly universally beloved, but they didn’t quite ignite the firestorm of controversy that MGS 2 set the gaming world ablaze with.

So what made Metal Gear Solid 2 different? Well…quite a few things, actually. However, if I had to identify one thing that really separated MGS 2 from the controversial sequels that game before, it would have to be the lengths that Hideo Kojima went to deliberately subvert players’ expectations in the name of pursuing what seemed to be a genuine artistic ambition.

Nearly every way that Metal Gear Solid 2 defied expectations was (in retrospect) done for a clear, creative-driven reason. Remember how I said that the game’s plot copies elements of MGS’ plot pretty much wholesale? Well, that’s because much of MGS 2’s story revolves around the idea that Raiden is being forced to undergo a kind of elaborate simulation of the events of the first game. Remember those long, rambling cutscenes? Some of those can be partially explained by the fact they’re actually being delivered by A.I. programs masquerading as humans. Others support the bigger narrative idea that Raiden (and, by extension, the player) isn’t actually in total control of their actions and are instead being driven along by the wills and suggestions of others.

Even Metal Gear Solid 2’s controversial protagonist switch was obviously done for a clear purpose. Partially inspired by the way that Terminator 2 defied fan expectations by turning the terminator into the protagonist, Kojima wanted to use Raiden to surprise fans. While some close to MGS 2 have also suggested that there were some thoughts that Raiden may be more appealing to female players and Japanese audiences, Kojima has always been very clear about why he put Raiden into the game.

“In a sequel, you have to meet people’s expectations, but you also sort of have to go against them and deceive them I think,” Kojima stated in Geoff Keighley’s The Final Hours of Metal Gear Solid 2 retrospective. “This is my Metal Gear, and I can destroy it if I want to.”

That’s what makes Metal Gear Solid 2 so fascinating. Kojima didn’t want to just surprise people; he wanted to deliberately deceive them and destroy the idea of expectations themselves. Whereas some previous subversive sequels either didn’t intentionally mislead audiences or only misled them because of questionable marketing, Kojima’s great artistic ambition was to point in one direction and lead everyone down another.

You can argue about whether or not Kojima succeeded in his mission to tell the great, subversive, meta-narrative he envisioned, but the execution of an idea is always subject to debate. What’s notable about Metal Gear Solid 2 is that it put the very idea of subverting expectations up for widespread public debate.

That’s a debate that we’re all too familiar with in the modern entertainment landscape. The Last Jedi, Iron Man 3, The Matrix Resurrections…it seems like every year features at least a handful of high-profile examples of a piece of entertainment that is defined more by the expectations it subverted than what it actually delivered.

The idea of “giving the fans what they want” has even become a populist talking point designed to (on some level) attack the works of those who tried to go against what was seemingly expected from them. The protagonist swap, in particular, has become an almost guaranteed source of controversy. Even generally acclaimed works like Mad Max: Fury Road endured a lot of blowback over their unexpected choice of protagonist.

Personally, I don’t think subverting expectations is a universally good or bad thing. What I do think is that Metal Gear Solid 2 really kicked an unfortunate era in which the fan backlash to subverted expectations is often the bigger talking point than the work itself. MGS 2 was also an early example of a piece of entertainment that drastically subverted expectations not just to troll people (though that was certainly part of it) but to attack the stagnate nature of franchises and pop culture in general.

Metal Gear Solid 2 Exposed the Growing Divide Between Fans and Critics

You may be wondering why people were so surprised by a “twist” in Metal Gear Solid 2 that makes up the vast majority of the game. Surely reviews and previews of the game must have given that major twist away, right?

Wrong. There were a few critics and online reporters at the time that addressed the big twist in Metal Gear Solid 2, but most publications didn’t even allude to it. Some went so far as to only use media from the part of the game that featured Snake. Others kind of talked around the twists as best as they were able.

More importantly, most critics at the time absolutely glowed about the game and gave it perfect (or nearly perfect) scores that fed the hype that it was going to be a universally beloved masterpiece. While there were some negative Metal Gear Solid 2 reviews that clearly took issue with the game’s creative choices, many reviewers seemed to be on board with Kojima’s decisions and went out of their way to keep them a secret. Here’s a particularly fascinating snippet from former GameSpot writer Greg Kasavin’s MGS 2 review that really captured how critics talked about the game during the pre-release period:

“If you take just one thing away from this review, then it should be this: Do not let anyone reveal the plot of Metal Gear Solid 2 to you, whether intentionally or inadvertently, before you play the game yourself…if you do happen to hear something about the story, don’t worry. Even if someone told you what The Matrix was really about, that still wouldn’t replace the experience of watching the movie. It’s a similar case with Metal Gear Solid 2, a game that can’t suitably be described in words, even if its plot twists can.”

Once Metal Gear Solid 2 was released to the public, it soon became clear that there were many who not only disagreed with the critic’s reviews but felt that the critics had intentionally deceived them as part of the “big lie” about the game. The cries of “conspiracy” could be heard in private conversations about the game as well as across many early internet message boards. There was this growing sentiment that players had not only been deceived by the developers but by the critics who had failed to do their jobs and properly report on the game’s secrets.

While I’d be lying to you if I tried to say that Metal Gear Solid 2 was the first example of a piece of entertainment that fans and critics disagreed on (it wasn’t even close), it was a very early example of a notable number of fans feeling that critics had intentionally deceived them in order to appease other interests. It was also a very early example of gamers using the internet to spread their fears of critical elitism and the idea that it was more important for gaming journalists to reveal everything about the game than it was to protect the “sanctity” of a fan’s experience.

Indeed, it’s kind of interesting to see how critics almost universally agreed to protect Metal Gear Solid 2’s secrets. Perhaps there was some kind of embargo in place, but it also seemed like many critics at the time were genuinely interested in the idea of protecting the game’s twists and turns so that everyone would get an equal chance to experience them for themselves. That’s a far cry from where we are at today. Now, you’re lucky if a movie, game, or TV show is out for an hour before your eyes are assaulted with spoiler-filled headlines.

Regardless, it’s that idea that Metal Gear Solid 2 reviewers chose the studio over gamers that has had the most lasting impact on popular culture. The very notion of a critic-lead conspiracy that separates entertainment journalists and fans was more popular in 2001 than it probably ever would have been in the pre-internet era. In 2022, you’re more surprised to see a critical darling not draw some kind of notable backlash from online fans, even if it’s only done in the name of spiting reviewers for their mere existence.

Metal Gear Solid 2 Should Be a Warning About the Power of Our Reactions

Was Metal Gear Solid 2 a good game? That’s obviously a subjective question, and, as we previously noted, the answer to that question has historically sometimes been less important than the impact of the backlash against MGS 2.

However, as someone who played Metal Gear Solid 2 when they were relatively young and honestly hated a lot of things about the game (mostly Raiden), I’ve found it interesting to watch the sequel be re-evaluated all these years later.

At the very least, I can tell you that Metal Gear Solid 2’s ideas about the importance of preserving art in the digital age, the weaponization of misinformation, and the illusion of control all went well over my head when I was younger yet feel all-too-relevant now. Mind you, I still don’t love MGS 2’s cutscene-heavy storytelling style (I’ve always struggled with that style when it comes to Kojima games), I think Raiden’s introduction and character growth were poorly handled, and some of the ways that the game uses “meta-commentary” as an excuse for its repetitiveness still bother me. Yet, the contempt I once had for the game has certainly been replaced by a lot of respect and some more nuanced criticisms.

Actually, for a game that brilliantly addressed the idea of the “echo chamber” in 2001, it’s oddly fitting that Metal Gear Solid 2 now teaches us a lesson about the dangers of overvaluing first reactions and how initial impressions don’t have to evolve into our core beliefs.

Anyone with access to the internet in 2001 probably had no trouble finding people who reacted just as negatively and just as swiftly to Metal Gear Solid 2 as they may have. I know I didn’t. Message boards were filled with fans expressing feelings of confusion, disappointment, anger, and even betrayal. Even in those early internet days, it was remarkably easy to find enough people to justify your gut reaction to pretty much anything. That problem has obviously only gotten worse as time has gone on.

Yet, both the plot of Metal Gear Solid 2 and the reactions to that game remind us that the power of the digital age doesn’t have to be limited to negatives. Over time, MGS 2 fans, dissenters, and everyone in-between have carved out a more complex legacy for the game that is worthy of such a complex title. Funnily enough, you may never know that people reacted as negatively towards the game as they once did given its modern online legacy as a misunderstood masterpiece that feels more important now than ever before.

So if there’s a positive lesson to take away from Metal Gear Solid 2’s “influence” on fan backlash, it’s that those gut reactions are a potentially lucrative, yet ultimately volatile, form of online and social currency. As more and more fans and creators begin to overvalue instant reactions, it’s important to realize the power they wield. Sometimes, it’s best to take a breath, wait, and realize that there are times when the works that deserve more complicated discussions are so often also the ones that can inspire the most visceral feedback.